In other posts I have looked at the partisan divides between, and demographic and cultural profiles, of ideological groups in contemporary Britain, and it seems that Left-Wing Progressives are particularly distinctive. Measures included in analysis of new survey data help to provide a much better account of that ideological group than its Mainstream Populist, Centrist, Moderate, or Right-Wing Populist counterparts. This raises questions of causality, which cannot be answered using cross-sectional survey data but require future attention.

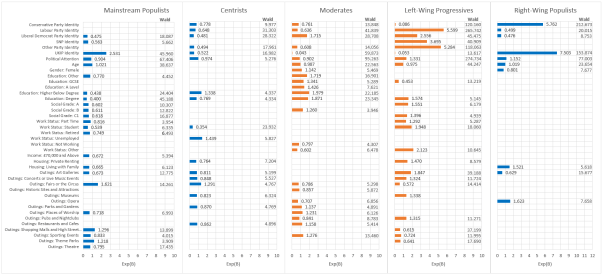

The model considered here was created to account for membership of five distinct ideological groups. This provided results indicating the specific relationships between variables (which can be seen in Chart 1 at the bottom of this post) but the focus here is on assessing the overall performance of the model in accounting for ideological position. With logistic regression this assessment is done with reference to the Cox & Snell R Square statistic. In this case, the figure indicates the extent to which the model accounts for whether or not respondents fall into each ideological group. Crucially, it is strikingly different for each of the ideological groups. At one end of the spectrum the figure for Centrists is 0.038, indicating that the variables included in the model are not, collectively, important factors in helping us understand why people are in that ideological group or not. At the other end of the spectrum the figure for Left-Wing Progressives is 0.309, indicating that the model is best at accounting for this ideological disposition and that people who hold such views are the most politically, socially, and culturally distinctive of the five groups that were considered.[1]

The performance of the model in relation to each of the ideological groups raises important issues of causality. What does it mean to say that the model ‘helps us understand’, or ‘is better at accounting for’, one ideological group or another? I have argued that ideology and party identity are likely to develop in relation to each other over time, and it is likely that they have their roots in early or formative years. This means that they may precede many of the demographic variables that were measured recently, such as current or recent work status, income, housing circumstances, cultural activities and possibly education. So, when statistically significant relationships are identified between those factors and ideological group, do we know whether one causes the other, vice versa, or just that they may be related in some way? The latter, most conservative, interpretation seems most convincing.

Therefore, whilst we can be confident that economic, social, and cultural circumstances have some relationship with political ideology, we cannot be equally confident of the causal direction of those relationships. Indeed, it may be that the model does not include key factors, some of which could be very difficult to measure, such as the ideological, cultural, or educational context that people were brought up in. The data do not contain information on the psychological experience that people had as they grew up, how their families and teachers expressed ideas or spoke about politics (if at all), or what educational priorities or cultural activities were emphasised (if any). Such factors may shape people’s subsequent ideological beliefs, party identities, educational levels, incomes, social grades, and cultural activities, amongst other things.

It seems likely that the ways in which people think about and understand the world shape their decision-making from an early age, and thus the circumstances in which they subsequently find themselves. At the same time, it is also plausible that such circumstances influence people’s beliefs about the world over their lifetime. This suggests the need to recognise both that circumstances influence and are influenced by beliefs, perhaps with some early circumstances and core beliefs having a lasting influence. However, these relationships cannot be disentangled using the cross-sectional data that underpin the models in question.[2] Thus, it has been shown that political ideology is intimately related to party identity and political attention, and that it is also related to background characteristics and cultural milieu. However, the question of precisely how economic, social, and cultural circumstances relate to political ideology remains open. Questions like this should be a key focus for research relating to political beliefs and behaviour. This is why the approach of the new Social Action as a Route to the Ballot Box project, using Understanding Society data, is so important, and why we need more such work.

[1] The figures for the other ideological groups are:

- Mainstream Populists: 0.114

- Moderates: 0.083

- Right-Wing Populists: 0.167

[2] The survey data that was gathered by YouGov for a research project on authoritarian populist ideologies that was led by Joe Twyman at Deltapoll. The results of that project were presented at the Professor Anthony King Memorial Conference at the University of Essex. Whilst the data underpinning the identified ideological clusters was gathered at the same time, the other background, political, and cultural variables were gathered previously and held by YouGov. Nevertheless, many of those variables are self-reported at a particular time and data on how they have developed over time or what their values were in the past is unavailable, meaning that I cannot conduct time-series analysis to investigate the relationships between variables over time.

1 thought on “In Britain, the Causes of Ideological Difference Remain Opaque”